Mutualisms: cooperation between species: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

\begin{array}{cc} | \begin{array}{cc} | ||

\label{eq:dg} | |||

\tag{1} | \tag{1} | ||

& C\qquad D\\ | & C\qquad D\\ | ||

\begin{matrix} | \begin{matrix} | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Thus, both players prefer mutual cooperation over mutual defection, yet defection yields the higher payoff regardless of what the partner does and hence the conflict of interest arises. | Thus, both players prefer mutual cooperation over mutual defection, yet defection yields the higher payoff regardless of what the partner does and hence the conflict of interest arises. | ||

Rescaling reduces the interaction in Eq. \eqref{eq:dg} to a single parameter: | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\label{eq:dgr} | |||

\tag{2} | |||

{\bf A}= | |||

\begin{pmatrix} 1-r & -r\\ | |||

1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, | |||

\end{equation} | |||

where \(r=c/b\) denotes the cost-to-benefit ratio with \(0\lt r\lt 1\). Moreover, for dynamics that only depend on payoff differences, a constant can be added to ensure that all payoffs are non-negative: | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\label{eq:dgr+} | |||

\tag{3} | |||

{\bf A}= | |||

\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0\\ | |||

1+r & r \end{pmatrix}. | |||

\end{equation} | |||

The problem of cooperation is exacerbated for actions that bestow benefits not just to other individuals but to those of another species. In particular it is crucial to clearly distinguish between the acts of cooperation of an individual and mutualistic interactions between individuals. Accomplishing mutually beneficial interactions requires coordination of cooperative acts between species. | The problem of cooperation is exacerbated for actions that bestow benefits not just to other individuals but to those of another species. In particular it is crucial to clearly distinguish between the acts of cooperation of an individual and mutualistic interactions between individuals. Accomplishing mutually beneficial interactions requires coordination of cooperative acts between species. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 54: | ||

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

\label{eq:re} | \label{eq:re} | ||

\tag{ | \tag{4} | ||

\dot x &= x(\xi_C - \bar\xi) = x(1-x)(\xi_C - \xi_D)\\ | \dot x &= x(\xi_C - \bar\xi) = x(1-x)(\xi_C - \xi_D)\\ | ||

\end{align} | \end{align} | ||

| Line 44: | Line 64: | ||

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

\label{eq:remut} | \label{eq:remut} | ||

\tag{ | \tag{5} | ||

\dot x &= x(\xi_C - \bar\xi)\\ | \dot x &= x(\xi_C - \bar\xi)\\ | ||

\notag | |||

\dot y &= y(\zeta_C - \bar\zeta), | \dot y &= y(\zeta_C - \bar\zeta), | ||

\end{align} | \end{align} | ||

| Line 53: | Line 74: | ||

Eq. \eqref{eq:remut} reduces to \(\dot x = x(1-x)(-c_x) \lt 0\) and \(\dot y = y(1-y)(-c_y) \lt 0\) such that in both species cooperators dwindle and eventually go extinct. Interestingly, this happens regardless of the magnitude of foregone benefits, \(b_x,b_y\). Thus, unsurprisingly the demise of cooperation in inter-species interactions remains unchanged. | Eq. \eqref{eq:remut} reduces to \(\dot x = x(1-x)(-c_x) \lt 0\) and \(\dot y = y(1-y)(-c_y) \lt 0\) such that in both species cooperators dwindle and eventually go extinct. Interestingly, this happens regardless of the magnitude of foregone benefits, \(b_x,b_y\). Thus, unsurprisingly the demise of cooperation in inter-species interactions remains unchanged. | ||

For simplicity we assume that species \(X\) and \(Y\) face the same donation game, with costs \(c=c_x=c_y\) and benefits \(b=b_x=b_y\). Thus, \(X\) and \(Y\) are interchangeable labels | For simplicity we assume that species \(X\) and \(Y\) face the same donation game, with costs \(c=c_x=c_y\) and benefits \(b=b_x=b_y\). Thus, \(X\) and \(Y\) are interchangeable labels. | ||

== Spatial populations == | == Spatial populations == | ||

Revision as of 01:29, 21 February 2025

In mutualistic associations two species cooperate by exchanging goods or services with members of another species for their mutual benefit. At the same time competition for reproduction primarily continues with members of their own species. In intra-species interactions the prisoner's dilemma is the leading mathematical metaphor to study the evolution of cooperation. Here we consider inter-species interactions in the spatial prisoner's dilemma, where members of each species reside on one lattice layer. Cooperators provide benefits to neighbouring members of the other species at a cost to themselves. Hence, interactions occur across layers but competition remains within layers. We show that rich and complex dynamics unfold when varying the cost-to-benefit ratio of cooperation, \(r\). Four distinct dynamical domains emerge that are separated by critical phase transitions, each characterized by diverging fluctuations in the frequency of cooperation: (i) for large \(r\) cooperation is too costly and defection dominates; (ii) for lower \(r\) cooperators survive at equal frequencies in both species; (iii) lowering \(r\) further results in an intriguing, spontaneous symmetry breaking of cooperation between species with increasing asymmetry for decreasing \(r\); (iv) finally, for small \(r\), bursts of mutual defection appear that increase in size with decreasing \(r\) and eventually drive the populations into absorbing states. Typically one species is cooperating and the other defecting and hence establish perfect asymmetry. Intriguingly and despite the symmetrical model setup, natural selection can nevertheless favour the spontaneous emergence of asymmetric evolutionary outcomes where, on average, one species exploits the other in a dynamical equilibrium.

The problem of cooperation

The evolution and maintenance of cooperation ranks among the most fundamental questions in biological, social and economical systems. Cooperators provide benefits to others at a cost to themselves. Cooperation is a conundrum because on the one hand everyone benefits from mutual cooperation but on the other hand individuals face the temptation to increase their personal gains by defecting and withholding cooperation. This generates a conflict of interest between the group and the individual, which is termed a social dilemma. The prisoner's dilemma is the most popular mathematical metaphor of a social dilemma and theoretical tool to study cooperation through evolutionary game theory.

Donation game

In the simplest and most intuitive instance of the prisoner's dilemma, the donation game, two players meet and decide whether to cooperate and provide a benefit \(b\) to their interaction partner at a cost \(c\) (\(b>c>0\)) or to defect, which entails no costs and provides no benefits. If both cooperate each gets \(b-c\) but if one defects then the defector gets \(b\) and shirks the costs of cooperation, while the cooperator is stuck with the costs \(-c\). Finally if both defect, no one gets anything. The interaction is conveniently summarized in a payoff matrix (for the row player):

\begin{array}{cc} \label{eq:dg} \tag{1} & C\qquad D\\ \begin{matrix} C\\D \end{matrix} & \begin{pmatrix} b-c & -c\\ b & 0 \end{pmatrix} \end{array}

Thus, both players prefer mutual cooperation over mutual defection, yet defection yields the higher payoff regardless of what the partner does and hence the conflict of interest arises.

Rescaling reduces the interaction in Eq. \eqref{eq:dg} to a single parameter:

\begin{equation} \label{eq:dgr} \tag{2} {\bf A}= \begin{pmatrix} 1-r & -r\\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \end{equation}

where \(r=c/b\) denotes the cost-to-benefit ratio with \(0\lt r\lt 1\). Moreover, for dynamics that only depend on payoff differences, a constant can be added to ensure that all payoffs are non-negative:

\begin{equation} \label{eq:dgr+} \tag{3} {\bf A}= \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0\\ 1+r & r \end{pmatrix}. \end{equation}

The problem of cooperation is exacerbated for actions that bestow benefits not just to other individuals but to those of another species. In particular it is crucial to clearly distinguish between the acts of cooperation of an individual and mutualistic interactions between individuals. Accomplishing mutually beneficial interactions requires coordination of cooperative acts between species.

Here we focus on the simplest setup with two identical species of equal population size each following the same ecological and evolutionary updating process.

Well-mixed populations

In intra-species interactions with random interactions, a so-called well-mixed population, the payoffs to cooperators and defectors soleley depends on their frequencies. In this case the replicator equation describes the change in the frequency of cooperators, \(x\), in a population as a function of the expected payoffs of cooperators and defectors, \(\xi_C\) and \(\xi_D\), respectively:

\begin{align} \label{eq:re} \tag{4} \dot x &= x(\xi_C - \bar\xi) = x(1-x)(\xi_C - \xi_D)\\ \end{align}

where \(\xi_C=x b-c\), \(\xi_D=x b\), and \(\bar\xi = x\xi_C+(1-x)\xi_D\) denotes the average payoff in the population. Since \(\dot x\lt 0\) for all \(x\), the frequency of cooperators decreases and eventually goes extinct. This is the well-known result that cooperation is not evolutionarily stable in the prisoner's dilemma.

In inter-species interactions it is of crucial importance to distinguish between cooperation -- costly acts of individuals that benefit others -- and mutualistic interactions, where both parties benefit from the interaction. For the inter-species donation game cooperators of one species, \(X\), provide benefits to members of another species, \(Y\), at a cost to themselves. In well-mixed populations, where members of one species interact with random individuals of the other species, the corresponding two-species replicator equation, for the frequencies of cooperators \(x\) in one species and \(y\) in the other, is given by

\begin{align} \label{eq:remut} \tag{5} \dot x &= x(\xi_C - \bar\xi)\\ \notag \dot y &= y(\zeta_C - \bar\zeta), \end{align}

where \(\xi_C=y b_x-c_x\) and \(\zeta_C=x b_y-c_y\) denote the expected payoffs for cooperators in species \(X\) and \(Y\) with costs \(c_x, c_y\) and benefits \(b_x, b_y\), respectively. Defectors equally reap the benefits but bear no costs, \(\xi_D=y b_x\) and \(\zeta_D=x b_y\), respectively. Note, the benefits to either species depend on the frequency of cooperators in the other species, who also bears the costs of cooperation. The average payoff to each species is \(\bar\xi = x \xi_C + y \xi_D = y b_x-x c_x\) and \(\bar\zeta = x \zeta_C + y \zeta_D = x b_y-y c_y\), respectively.

Eq. \eqref{eq:remut} reduces to \(\dot x = x(1-x)(-c_x) \lt 0\) and \(\dot y = y(1-y)(-c_y) \lt 0\) such that in both species cooperators dwindle and eventually go extinct. Interestingly, this happens regardless of the magnitude of foregone benefits, \(b_x,b_y\). Thus, unsurprisingly the demise of cooperation in inter-species interactions remains unchanged.

For simplicity we assume that species \(X\) and \(Y\) face the same donation game, with costs \(c=c_x=c_y\) and benefits \(b=b_x=b_y\). Thus, \(X\) and \(Y\) are interchangeable labels.

Spatial populations

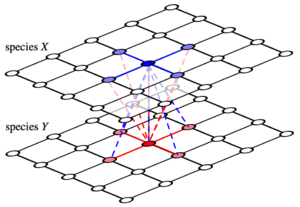

In order to delineate effects of spatial dimensions on cooperation in mutualistic interactions, we consider two parallel, square lattice layers with \(N=L \times L\) sites each, where \(L\) refers to the linear lattice dimension. Each site is occupied by one individual with \(k=4\) neighbours under periodic boundary conditions. One layer represents species \(X\) and the other species \(Y\): individuals in each layer interact with their \(k+1\) nearest neighbours on the other layer but compete with \(k\) neighbours in their own layer, see figure.

Dynamical domains

In spatial settings the formation of clusters reduces exploitation and increases interactions with other cooperators to make up for losses against defectors. Spatial assortment enables co-existence. This results in four dynamical domains depending on the cost-to-benefit ratio of cooperation, \(r\):

- \(r>r_1\): defection dominates. For high costs or low benefits, spatial correlations are insufficient to support cooperation and both populations evolve towards the absorbing \(DD\) state. The outcome is the same as in well-mixed populations, see \eqref{eq:remut}.

- \(r_2<r<r_1\): cooperators and defectors co-exist. The frequency of cooperators in the dynamical equilibrium is equal in both layers and increases for decreasing \(r\).

- \(r_3<r<r_2\): spontaneous symmetry breaking. Cooperators and defectors continue to co-exist in a dynamical equilibrium but with essentially complementary strategy frequencies in the two layers.

- \(0<r<r_3\): relaxation into asymmetric absorbing states \(CD\) or \(DC\). The emergence, growth and elimination of homogeneous domains of defection (\(DD\) regions) drive spikes (or bursts) in defector frequencies.

The four dynamical regimes are separated by three different types of critical phase transitions.

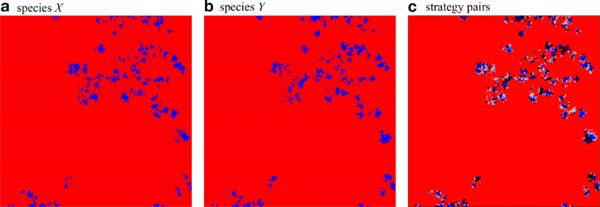

Symmetric cooperation: random walk

The spatial configuration of cooperators, \(\blacksquare\), and defectors, \(\blacksquare\) for each species separately, a and b, as well as for strategy pairs, c, with \(CC\) \(\blacksquare\), \(DD\) \(\blacksquare\), \(CD\) \(\blacksquare\) and \(DC\) \(\blacksquare\) in the symmetric phase close to but below the directed percolation threshold, \(r=0.0225<r_1\): Strongly correlated clusters of cooperators on both layers perform a coordinated branching and annihilating random walk. Parameters: \(200\times200\) region of a \(1000\times1000\) lattice with \(K=0.1\). Click image for interactive online simulations.

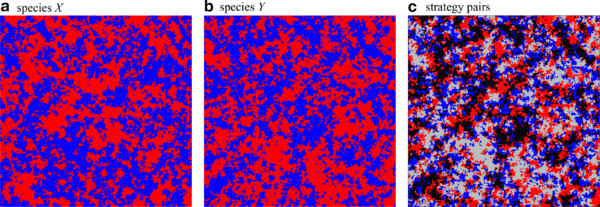

The spatial configuration of cooperators, \(\blacksquare\), and defectors, \(\blacksquare\) for each species separately, a and b, as well as for strategy pairs, c, with \(CC\) \(\blacksquare\), \(DD\) \(\blacksquare\), \(CD\) \(\blacksquare\) and \(DC\) \(\blacksquare\) in the symmetric phase close to but above the symmetry breaking, \(r=0.005>r_2\): Almost identical frequencies of cooperators and defectors establish in both layers. The similar frequencies of all four strategy pairs indicate that the layers are essentially uncorrelated. Switching the labels of species \(X\) and \(Y\) in a, b merely switches the role of \(CD\) and \(DC\) pairs, \(\blacksquare\) \(\leftrightarrow\blacksquare\). Parameters: \(200\times200\) region of a \(1000\times1000\) lattice with \(K=0.1\).

Asymmetric cooperation

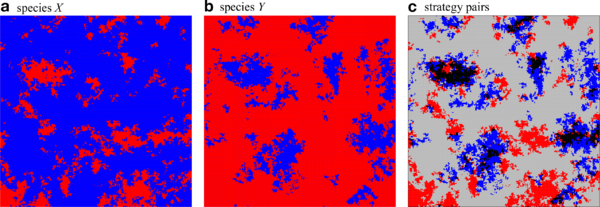

Typical spatial strategy distribution in the asymmetric phase with essentially complementary frequencies and distributions of cooperators and defectors in the two layers. Parameters are the same as in the previous figures but with \(r=0.0015\).

Bursts of defection

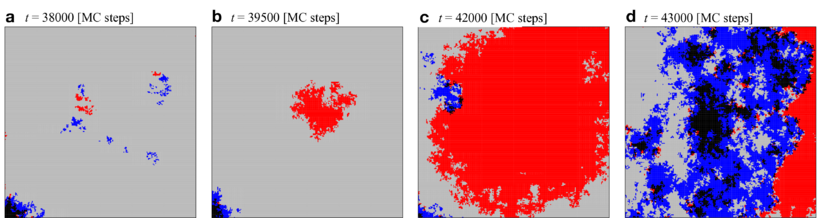

Snapshots a-d illustrate the spatial distribution of the four strategy pairs between lattices, \(CC\) \(\blacksquare\), \(DD\) \(\blacksquare\), \(CD\) \(\blacksquare\) and \(DC\) \(\blacksquare\), during a \(DD\) burst within a \(240\times240\) region of a \(1000\times1000\) lattice.

First, small islands of \(CC\) and \(DD\) pairs move, collide, and disappear at random in a large domain of \(CD\) pairs (a). These islands are continuously created along the boundary separating large \(CD\) and \(DC\) domains (a lower left corner). Most islands eventually go extinct. Only sufficiently large \(DD\) areas occasionally expand (b). The \(DD\) domain grows until it collides with a small \(CC\) island, which invades its territory (c). However, the \(CC\) domains are not stable against invasion of \(CD\) or \(DC\) phases (d). Subsequently, the strategy distribution evolves slowly toward the initial distribution (a).

Conclusions & Discussion

Interactions between species play a crucial role in symbiotic associations. More specifically, in mutualistic exchanges members of one species provide benefits in the form of goods or services to members of another species and vice versa. For costly provisions this results in an inter-species donation game but with a more fragile arrangement than for the standard, intra-species donation game. Here we studied the evolution of costly acts of cooperation on a two-layer square lattice, where each layer represents one species. This models a basic two-species ecological system. Evolution is controlled by increased reproduction or imitation of fitter neighbours within the same layer, while the payoff (or fitness) of individuals is determined through interactions between layers.

Using numerical simulations, we determined the frequency and fluctuation of cooperation in both layers as a function of the cost-to-benefit ratio, \(r\). This reveals three distinct critical phase transitions:

- for \(r \to r_1\) from below, cooperation goes extinct in both layers simultaneously following the directed percolation universality class. Surprisingly, the extinction threshold \(r_1\approx0.02283(3)\) is very similar to the threshold in single species interactions \(r\approx0.0261\) (estimated from Szabó & Hauert, 2002). Even though conditions for cooperation would seem much more challenging in interactions across species.

- spontaneous symmetry-breaking arises in the frequency of cooperation on the two layers when \(r \to r_2\). In fact, two equivalent asymmetric phases exist where individuals in one layer prey on those in the other layer or vice versa. This phase transition is similar to the spontaneous symmetry breaking in the two-dimensional Ising model in the absence of an external magnetic field. Although, the additional degrees of freedom (four instead of two microscopic states) result in deviations in the fluctuations of cooperation frequencies.

- The third critical transition occurs for \(r \to r_3\) from above and is driven by bursts of \(DD\) domains. For small \(r\) the magnitude of the symmetry breaking decreases with \(r\), while the magnitude of bursts increases and causes fluctuations to diverge. However, the identification of the universal features of bursts and the slow transition towards absorbing states requires further, time-consuming simulations and analytical investigations.

From a dynamical systems perspective this last critical transition is the most intriguing feature of our model. It poses a challenge for understanding the underlying mechanisms that characterize this universality class and drive the observed power law behaviour. Conversely, from a more applied, biological or social perspective, the spontaneous symmetry breaking and the dynamics of the asymmetric phase are equally clearly the most relevant and compelling feature. In particular, the mechanism for generating and maintaining the asymmetric phase appears to be intrinsically linked to the spikes in defection observed for \(r\to r_3\). More specifically, the emergence of asymmetries is driven by cyclical invasions of locally homogeneous domains: \(CD\), \(DC\) invade \(CC\) invades \(DD\) invades \(CD\), \(DC\) etc. This cycle becomes increasingly pronounced for decreasing \(r\) because the local domains grow and eventually give rise to the global spikes in defection that characterize the third critical transition. Assuming more \(C\)'s in one layer, the invading \(CC\) domains are more likely to encounter a \(D\) in the other layer, which then amplifies the asymmetry.

Symmetry breaking in the frequencies of cooperation between species has been reported before (see Ezoe & Ikegawa, 2013). However, the characteristics of the species association is not merely determined by the strategy frequencies but rather by the pairings of individual strategies across layers: mutualistic (\(CC\) pairings), exploitative/parasitic (\(CD\), \(DC\) pairings) or non-existent (\(DD\) pairings), i.e. no exchange of goods or services. In social dilemmas individuals fail to achieve the socially optimal outcome out of self interest. Cooperation in mutualistic interactions between species takes more varied forms than in interactions within species. Intriguingly, even in fully symmetrical mutualistic interactions, natural selection may favour asymmetric states where one species exploits the other. The resulting unfair cost allocation is reminiscent of the continuous snowdrift game in intra-species interactions, where evolution can promote the emergence of distinct cooperator and defector traits and spatial settings further promote the diversification into distinct traits (see Hauert & Doebeli, 2021).

In the asymmetric phase, one species produces a social good at much higher rates than the other, which effectively separates the two species into producers and consumers. Interestingly, however, the average level of cooperation across both layers remains essentially constant at \(50\%\). Both species produce social goods but the consumers produce theirs at much lower rates. Nevertheless, exploitation in this dynamical equilibrium is limited both spatially and temporally. In the long run, every individual produces one good and receives the other. Surprisingly, this asymmetry tends to become more pronounced for higher stakes, that is for decreasing cost-to-benefit ratios. Although the social dilemma becomes more benign and defection less tempting, the inequalities between species culminate in full exploitation under the most benign conditions.

Critical phase transitions

The social dilemma in Eq. \eqref{eq:dgr} is in effect for \(r>0\) and \(D\) dominates (mutual defection is the sole Nash equilibrium). However, in spatial settings homogeneous defection results only for sufficiently large \(r>r_1\approx0.02283(3)\). For smaller \(r\), the limited local interactions suffice to protect cooperators. The formation of clusters reduces exploitation and increases interactions with other cooperators to make up for losses against defectors. Spatial assortment enables co-existence. More specifically, four dynamical regimes exist that are separated by critical phase transitions at \(r_1\), \(r_2\), and \(r_3\).

Each critical phase transition is characterized by, indeed defined by, diverging properties, such as fluctuations or correlation times and lengths. As a consequence it is numerically challenging to determine the exact transition points because the diverging quantities require both large lattices as well as long averaging times.

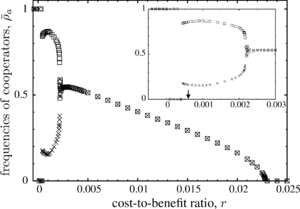

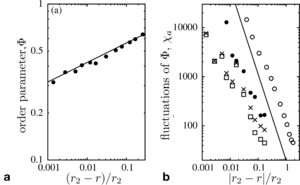

Overall, the frequency of cooperation tends to increase as the conditions of cooperation become more benign, i.e. lower costs or higher benefits, which translates into smaller ratios \(r\) (as shown on the right). For large \(r\) the frequency of cooperation is the same in both lattices. This is not surprising because of the symmetrical setup. However, when decreasing \(r\) cooperation becomes less challenging and a surprising spontaneous break of the symmetry is observed, which results in essentially complementary frequencies of cooperators and defectors in the two lattices.

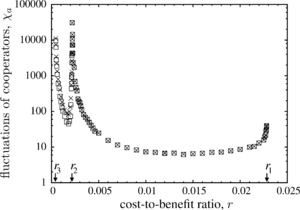

In order to determine the boundaries \(r_1\), \(r_2\), and \(r_3\) of the dynamical domains in descending order of \(r\), as well as to classify the accompanying phase transitions, we consider the fluctuations, \(\chi_a\), in the frequency of cooperation in in layer \(a\):

\begin{align} \chi_a &= N \langle\left(\rho_a(t) - \bar\rho_a\right)^2 \rangle . \label{eq:chiav} \end{align}

Note that \(\chi_a\) becomes constant in the limit \(N\to\infty\) and \(\chi_a=0\) holds for homogeneous states. The scaling of \(\chi_a\) as \(r\) approaches a critical phase transition helps to identify the corresponding universality class. The large fluctuations that accompany and indeed characterize the critical phase transitions, require significantly larger lattices (up to \(L=1800\) with \(\tau_s>10^7\), \(\tau_r=2\cdot10^6\)).

Directed percolation

Near the extinction threshold, \(r_1\), isolated clusters of cooperators perform a branching and annihilating random walk with almost perfect correlations between lattices. The characteristic spatial patterns are captured by snapshots of the configuration in each lattice as well as the pair distributions (see lab on Symmetric cooperation: random walk).

Coordination between lattices is almost perfect with very few \(CD\) and \(DC\) pairs. This is of the essence for the survival of cooperation. \(CC\) interactions are the bulwark against, or at least help to compensate for exploitation by defectors. Interestingly, the emerging spatial configurations are very similar to those in the intra-species donation game on a single lattice.

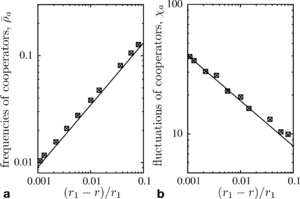

In agreement with theoretical expectations the critical transition at \(r_1\) clearly belongs to the two-dimensional directed percolation universality class: in both layers the frequency of cooperation scales with \(\bar\rho_a \propto (r_{1}-r)^\beta\) for \(\beta=0.580(3)\) and their fluctuations scale with \(\chi_a \propto (r_{1}-r)^{-\gamma}\) for \(\gamma=0.35(1)\) when \(r\to r_1\) from below (as shown on the right)

When lowering the cost-to-benefit ratio, \(r_2<r<r_1\), the frequency of cooperation gradually increases with decreasing \(r\), while the coordination between layers decreases. For \(r\) close to \(r_2\) the frequency of all four strategy pairs are essentially the same, which supports that configurations are largely uncorrelated (see lab on Symmetric cooperation: uncorrelated).

Spontaneous symmetry breaking

Intriguingly, lowering \(r\) further to \(r_3<r<r_2\) with \(r_3\approx0.00041(3)\) results in spontaneous symmetry breaking with different frequencies in each layer (see lab on Asymmetric cooperation).

The distribution of cooperators and defectors in each layer is almost complementary. Clusters, or regions of cooperators, in one layer are matched by defectors in the other. As a consequence, the lattices consist mostly of \(CD\) and \(DC\) pairs. Because of the distinctly different frequencies of cooperation in each lattice, either \(CD\) or \(DC\) pairs dominate. However, note that which pair dominates is of no consequence, because species interactions are symmetric, and hence it is merely a consequence of which species is labelled \(X\) and which \(Y\). Defectors in one species manage to exploit and take advantage of cooperators in the other species. However, exploitation is ephemeral and the scale is limited both spatially as well as temporarily.

In the vicinity of the symmetry breaking transition, \(r_2\), technical difficulties can arise in Monte Carlo simulations through the formation of strip-like domain structures that persist for long times at low noise. Moreover, if both layers are initialized with the same frequency of \(C\) players, the probability to end up with more \(C\) players is equal for both layers. Albeit only after a slow domain growing process studied well for Ising models. Fortunately, such difficulties can be easily prevented by starting from initial configurations with different \(C\) frequencies in each layer.

Our analysis of the spontaneous symmetry breaking borrows concepts from the Ising model and critical phase transitions. The two-dimensional Ising model exhibits universal features through the power law scaling of the spontaneous magnetization in the absence of an external magnetic field, as well as the accompanying fluctuations when the temperature approaches the critical point. Here we use \(r\) instead of the temperature as the control parameter and, instead of the magnetization as the order parameter, we use the asymmetry in cooperation between the two layers \(\Phi=|\bar\rho_{+1}-\bar\rho_{-1}|\). The scaling of the order parameter, \(\Phi\), and its fluctuations for \(r \to r_2\) clearly shows the expected power law behaviour and its fluctuations are in line with the theoretical predictions of \(|r-r_2|^{-\gamma}\) and \(\gamma=7/4\) within the accuracy of our MC data (shown on the right).

However, the equivalence to the universal features of Ising type transitions is not obvious. Additional degrees of freedom result from the larger number of possible strategy pairs (\(CC, CD, DC\), and \(DD\)) across the two layers. In order to illustrate the consequences, the scaling of fluctuations of cooperation are shown for each layer separately.

Bursts of defection

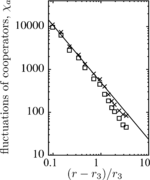

Finally, for \(0<r<r_3\), the population relaxes into one of its four absorbing states depending on the initial configuration. In fact, the most striking dynamical phenomenon of this model manifests itself in the diverging fluctuations of \(C\) frequencies, \(\chi_a\), for \(r\to r_3\) (see lab on Bursts of defection).

In particular, no theoretical arguments exist to date that explain and justify the observed power law behaviour of \(\chi_a \propto (r-r_3)^{-\gamma}\) for \(r\to r_3\) from above with \(\gamma=1.33(5)\). The divergence of \(\chi_a\) is related to the emergence, growth and elimination of homogeneous \(DD\) domains. Spikes in \(DD\) frequencies drive the dynamics of bursts.

This type of bursts are driven by sufficiently large spatial domains of an unstable phase. Evidently, their extension and frequency depends on \(r\) and other parameters. In particular, bursts become larger and rarer when decreasing \(r\). Once a burst reaches sizes comparable to the entire lattice, it can drive the evolution towards absorbing states. Interestingly, the absorbing \(DD\) state is rarely observed because it is prone to invasion by any remaining \(CC\) islands, which then pave the way for \(CD\) or \(DC\) phases to grow and take over. This is in stark contrast to intra-species models where cooperation continuously increases for decreasing \(r\), that is as the social dilemma becomes more benign.

Another peculiarity of the burst dynamics is the feedback between their creation and extinction and the spatial configuration of the asymmetric phase: for \(r\) close to \(r_3\), the asymmetry of cooperation, \(\Phi = |\bar\rho_{+1} - \bar\rho_{-1}|\), decreases with \(r\) while the burst sizes increase.

For \(r<r_3\) the population tends to get absorbed in the fully asymmetric \(CD\) or \(DC\) states. Once one layer is homogeneous the dynamics in the other layer is dominated by neutral drift because the difference in payoffs between cooperators and defectors merely amounts to \(4r\). Hence, for small \(r\), the probability to update the strategy essentially reduces to a coin toss with a slight bias in favour of defectors. The probability to fixate in one or the other absorbing state is thus essentially given by the frequency of strategies in the heterogeneous layer at the time the other layer turned homogeneous. For example, if one layer becomes homogeneous in \(C\), then the frequency of \(C\)’s in the other layer is likely \(<1/2\), due to the asymmetry. Thus, the \(CD\) absorbing state is more likely than \(CC\). Conversely, if one layer becomes homogeneous in \(D\), then the frequency of \(C\)’s in the other layer is likely \(>1/2\) and hence the \(DC\) absorbing state is more likely than \(DD\). Finally, it is more likely that one layer becomes homogeneous in \(D\) because isolated \(C\)’s (or small \(C\) clusters) are more easily eliminated than \(D\)’s. Thus, even though all four absorbing states may be reached, in principle, the probabilities to do so are very different and most likely the populations approach heterogeneous absorbing states, whereas homogeneous cooperation across lattices is a highly unlikely outcome.

Publications

- Hauert, C. & Szabó, G. (2024) Spontaneous symmetry breaking of cooperation between species, PNAS Nexus (in print) doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae326

References

- Ezoe H. & Ikegawa Y. (2013) Coexistence of mutualists and non-mutualists in a dual-lattice model J. their. Biol. 332 1-8.

- Szabó, G. & Hauert, C. (2002) Phase Transitions and Volunteering in Spatial Public Goods Games, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 (11) 118101.

- Hauert, C. & Doebeli, M. (2023) Spatial social dilemmas promote diversity Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118 (42) e2105252118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2105252118.