Evolutionary graph theory

Evolutionary dynamics act on populations. Neither genes, nor cells, nor individuals but populations evolve. In small populations, random drift dominates, whereas large populations are sensitive to subtle differences in selective values. Traditionally, evolutionary dynamics was studied in the context of well-mixed or spatially extended populations. Here we generalize population structure by arranging individuals on a graph. Each vertex represents an individual. The fitness of an individual denotes its reproductive rate, which determines how often offspring is placed into adjacent vertices.

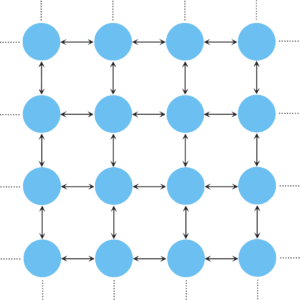

Popular population structures include well-mixed (or 'unstructured') populations, which correspond to fully connected (or complete) graphs or populations with spatial dimensions that are represented by lattices. Other, more general population structures include small-world or scale-free networks.

The stochastic dynamics of selection and random drift is traditionally modelled by the Moran process for finite, unstructured (well-mixed) populations. This process has the nice, i.e. mathematically convenient, feature that the population size is preserved and is easily adapted to model evolutionary processes in structured populations, the Spatial Moran process.

In the following, we study the simplest possible question: what is the probability that a single mutant generates a lineage that takes over the entire population? This fixation probability determines the rate of evolution. The higher the correlation between the mutant's fitness and its probability of fixation, the stronger the effect of natural selection; if fixation is largely independent of fitness, drift dominates.

A large class of graphs exhibit a characteristic balance between selection and drift as characterised by the circulation theorem. Nevertheless, the structure of the graphs can have tremenduous effects on the fixation probability of mutant ranging from complete suppression of selection to complete suppression of random drift, i.e. amplification of selection. If, in addition, individuals interact with their neighbors, reflecting frequency dependent fitness, the dynamics becomes very complicated but first studies show very interesting and counterintuitive results.

Moran graphs

Population structure can be introduced by assuming that the individuals occupy the nodes of a graph. The adjacency matrix \(W = [w_{ij}]\) then determines the structure of the graph, where \(w_{ij}\) denotes the probability that individual \(i\) places its offspring into node \(j\). If \(w_{ij} = w_{ji} = 0\) then the nodes \(i\) and \(j\) are not connected. Interestingly, the fixation probability remains unaffected for a large class of population structures (graphs known as circulations), i.e. is the same as for the original Moran process in unstructured populations. For a single mutant this is \[ \rho_1 = \frac{\displaystyle 1-\frac1r}{\displaystyle 1-\frac1{r^N}}. \] and does not depend on the initial location of the mutant. This applies, for example, for the fixation probabilities of mutants on lattices.

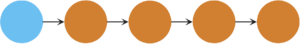

Evolutionary suppressors

The characteristic balance between selection and drift in Moran graphs can tilt to either side for graphs that are not circulations. For example, suppose \(N\) individuals are arranged in a linear chain. Each individual places its offspring into the position immediately to its right. The leftmost individual is never replaced. The mutant can only reach fixation if it arises in the leftmost position, which happens with probability \(1/N\), but then it will eventually reach fixation with certainty. Clearly, for such one-rooted graphs the fixation probability of a single, randomly placed mutant is \[ \rho_0 = \frac1N, \] irrespective of \(r\). The chain is an example of a simple population structure which eliminates selection and whose dynamic is determined by random drift.

Evolutionary amplifiers

Interestingly, it is also possible to create population structures that amplify selection and suppress random drift. For example, on the star graph, where all nodes are connected to a central hub and vice versa, the fixation probability of a single, randomly placed mutant becomes \[ \rho_2 = \frac{\displaystyle 1-\frac1{r^2}}{\displaystyle 1-\frac1{r^{2N}}}. \] for large \(N\). Thus, any selective difference \(r\) is amplified to \(r^2\). Even more intriguingly, population structures exist that act as arbitrarily strong amplifiers of selection and suppressors of random drift. However, note that amplification has its price in that the average fixation time goes to infinity as the amplification increases.

Publications

- Lieberman, E., Hauert, C. & Nowak, M. (2005) Evolutionary dynamics on graphs Nature 433 312-316 doi: 10.1038/nature03204.

- Hauert, C. (2008) Evolutionary Dynamics p. 11-44 in Evolution from cellular to social scales eds. Skjeltorp, A. T. & Belushkin, A. V., Springer Dordrecht NL.

- Jamieson-Lane, A. & Hauert, C. (2015) Fixation probabilities on superstars, revisited and revised J. Theor. Biol. 382 44-56 doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.06.029.

Press & News

- Guimerà, R. & Sales-Pardo, M. (2006) Form follows function: the architecture of complex networks Molecular Systems Biology 2 42 doi: 10.1038/msb4100082.